What is Python¶

The official description of python is:

Python is an interpreted, object-oriented, high-level programming language with dynamic semantics. Its high-level built in data structures, combined with dynamic typing and dynamic binding, make it very attractive for Rapid Application Development, as well as for use as a scripting or glue language to connect existing components together. Python’s simple, easy to learn syntax emphasizes readability and therefore reduces the cost of program maintenance. Python supports modules and packages, which encourages program modularity and code reuse. The Python interpreter and the extensive standard library are available in source or binary form without charge for all major platforms, and can be freely distributed.

All that to say that Python is an open-source programming language that is easy to read, easy to write and fast to develop.

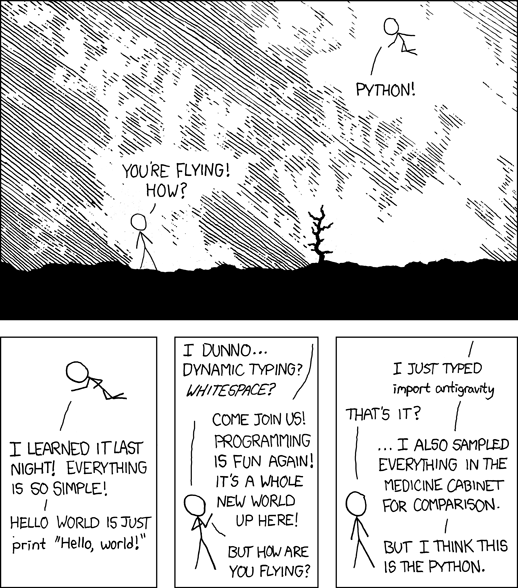

Perhaps python best described in XKCD by Randell Munroe:

p.s. in a console type import antigravity and see what happens.

Using python for environmental science has several advantages over traditional means:

- It’s free and doesn’t need a licence. The skills you learn in python can be used everywhere.

- Repeatability. Anyone on earth can reproduce your analysis, which is the fundamental goal of science.

- Speed and efficiency. Do the work once and reuse the code.

- Automation. Take the soul sucking tasks and give them to a non-sentient being (and no, we’re not talking about a grad)

- Big data. Only with a programming language can you manage the big data that’s rapidly becoming the norm.

- Interactive systems. Python allows interactive plotting, reporting, and systems that simply are not possible in traditional systems.

- Community. There is an enormous online community of scientific python users as demonstrated by Programming: Pick up Python

A brief history of python¶

Guido Van Rossum published the first version of Python code (version 0.9.0) at alt.sources in February 1991. The creation of python was heavily influenced by the development of the programming language ABC. Since then it as seen explosive growth to become one of the most common programming languages in the world.

What about the name python? Guido van Rossum, the creator of Python wrote “Over six years ago, in December 1989, I was looking for a ‘hobby’ programming project that would keep me occupied during the week around Christmas. My office … would be closed, but I had a home computer, and not much else on my hands. I decided to write an interpreter for the new scripting language I had been thinking about lately: a descendant of ABC that would appeal to Unix/C hackers. I chose Python as a working title for the project, being in a slightly irreverent mood (and a big fan of Monty Python’s Flying Circus).”

Python versions¶

There are currently two main versions of python - Python 2 and Python 3. Python 3 is the branch that is being actively developed, while Python 2 only has legacy fixes. Python 2 only exists because Python 3 was not backwards compatible with Python 2. All new programmers should go straight to Python 3 unless there’s a really good reason (e.g. legacy packages in 2.7). The current stable version is Python 3.6, which is the version we will use in this course.

Interactive python, running scripts and IDEs¶

Interactive python¶

Python has the option to run in an interactive mode. This way every command that you enter is executed and you immediately see the output. This is a great way to play around with commands in python and build some simple knowledge, but it is quite limiting when it comes to doing complicated analysis.

Running scripts¶

You can also package up your python commands into a script (basically a text file ending with .py). To run the script on windows you can execute it with the command prompt: path_to_pythonpython.exe path_to_script.py. This will then run through all of the commands in the python script. The advantages to running a script rather than doing work through interactive python is that you keep all of your work. Your project effectivly documents itself. This is really the best practice for good repeatable science.

IDEs¶

People often find that writing python scripts in notepad or similar can be a bit tedious. Instead environmental scientists often turn to integrated development editors or IDEs. An IDE normally consists of a source code editor, build automation tools, and a debugger. Most modern IDEs also have intelligent code completion, which makes scripting much quicker.

IDEs are essentially the programmers equivilant of a Harry Potter wand. Google IDEs and there are certainly lots of strong opinions. Regardless of which IDE you end up with (and you will certainly end up with one of them), there are some important considerations. IDE’s make it easy to pass code from a script editor into a console, which is really useful for debugging and testing things as you develop them. Despite this you must never:

- create a finished script that runs different things based on the lines that you comment out.

- create a finished script that relies on some other command being run in an interactive python console.

- create a finished script that relies on commands being run in some order other than the order that they are written in.

- create a finished script that relies on some lines of code not being run.

The reason for these four rules is code repeatability. One of the biggest advantages to science in any programming language is that given the inputs anyone (including yourself) can replicate the work that you’ve completed. Break any of the aforementioned rules and it is usually quicker to redo the work from scratch than use the code you’ve produced.

As far as specific IDEs we would recommend that people start with Spyder because it is a relatively lightweight IDE that is open source and comes with the anaconda build that you have already installed. As time goes on, particularly once you start developing tools then keep your eye out for other IDEs just in case they suit you better. We won’t give suggestions, it’s better to simply ask around - someone will have an opinion.

Philosophy of coding, The Zen of Python, and pep8¶

Philosophy of coding¶

For new comers to python (or any programming language) some useful tips:

- Make lots and lots of mistakes. Red on the screen isn’t a failure, it’s a natural part of the process.

- You are probably not making more mistakes, you’re just catching more of them.

- Document everything. Comments (started with the #) are your friend.

- Accept that things will take longer in the short term, but shorter in the long term.

The Zen of Python¶

Long time Pythoneer Tim Peters succinctly channels the Benevolent Dictator for Life’s guiding principles for Python’s design into 20 aphorisms, only 19 of which have been written down.

- Beautiful is better than ugly.

- Explicit is better than implicit.

- Simple is better than complex.

- Complex is better than complicated.

- Flat is better than nested.

- Sparse is better than dense.

- Readability counts.

- Special cases aren’t special enough to break the rules.

- Although practicality beats purity.

- Errors should never pass silently.

- Unless explicitly silenced.

- In the face of ambiguity, refuse the temptation to guess.

- There should be one– and preferably only one –obvious way to do it.

- Although that way may not be obvious at first unless you’re Dutch.

- Now is better than never.

- Although never is often better than right now.

- If the implementation is hard to explain, it’s a bad idea.

- If the implementation is easy to explain, it may be a good idea.

- Namespaces are one honking great idea – let’s do more of those!

Pep8¶

There is a documented style guide for python; it’s called PEP8. While following PEP8 isn’t necessary, it does make for much more readable (and thus less error prone) code. Through this course we will try our best to follow pep8 and as you start to write scripts we’d encourage you to start taking it on board.